Fungalpedia – Note 261, Valdensia

Valdensia Peyronel.

Citation when using this entry: Aumentado et al. 2024 (in prep) – Fungalpedia, plant pathogens.

Index Fungorum, Facesoffungi, MycoBank, GenBank, Fig. 1.

Classsification: Sclerotiniaceae, Helotiales, Leotiomycetidae, Leotiomycetes, Pezizomycotina, Ascomycota, Fungi

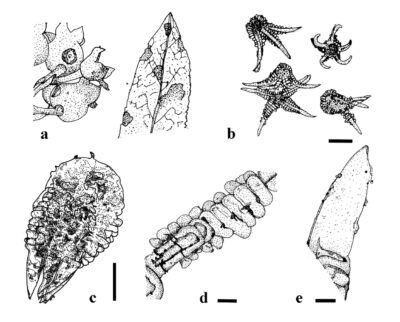

Valdensia was introduced by Peyronel (1923) and typified with Valdensia heterodoxa. Valdensia (asexual) and Valdensinia (sexual) have the same type of species and are generic synonyms; however, including Asterobolous, Johnston et al. (2014) proposed to conserve the former over the latter. This monotypic genus is characterised by its star-shaped conidia (stauroconidia), which are stellate, thick-walled, range from hyaline to pale brown, and are typically surrounded by a whorl of four or five appendages (Nekoduka et al. 2012) to three to six (Abbasi et al. 2023). Conidia have a single row of 8–10 closely spaced, thin-walled, transverse swellings on the proximal sections of the upper surfaces of the appendages, whereas the distal portion of the appendages is subulated and sparsely granulated. As the conidia matured, the appendages folded completely, resulting in a teardrop shape. The hemispherical conidial head consists of approximately 150 cells that germinate to produce infective hyphae (Redhead & Perrin 1972), and are coated with mucus, facilitating adhesion to leaf surfaces (Abbasi et al. 2023). Multiple germ tubes with branched appressoria emerge from the conidial head to infect host tissues (Norvell & Redhead 1994, Zhao and Shamoun 2006, Nekoduka et al. 2012). Single conidia, recently infecting a leaf, are often visible to the naked eye at the center of lesions (Redhead and Perrin 1972, Hildebrand and Renderos 2007, Nekoduka et al. 2012). The ITS molecular sequence data are available (Nekoduka et al. 2012, Kukula et al. 2017).

Since the initial documentation of Valdensia in Italy (Peyronel 1923) that affected Vaccinium myrtillus L., it has subsequently been observed in various European countries, Russia, Japan, and North America, infecting over 60 plant species (Peyronel 1927, Gjerum 1970, Redhead 1979, Norvell & Redhead 1994, Mulenko & Woodward 1996, Melnik et al. 2007, Mulenko et al. 2008, Nekoduka et al. 2012, Dzięcioł et al. 2014, Farr & Rossman 2024). However, it is primarily associated with hosts of the Ericaceae family, including Vaccinium and Gaultheria as reported by several studies (Mulenko & Woodward 1996, Nekoduka et al. 2012, Abbasi et al. 2023). The primary symptoms manifest as circular, desiccated patches on the leaves, often encircled by a brown or reddish ring, and the colour intensity is influenced by sunlight exposure (Peyronel 1923, Hildebrand & Renderos, 2017). It is hypothesised that anthocyanins produced in infected leaves exposed to light contribute to the leaf’s resistance against fungal activity, resulting in smaller spots compared to shaded plants (Peyronel 1923).

Pathogenicity assays in Vaccinium spp. resulted in an infection success rate of more than 50% (Lyon et al. 2015), whereas assays by Nekoduka et al. (2012) and Kukula et al. (2017) caused small necrotic lesions on young detached leaves of Vaccinium spp. that developed into large rings. Norvell & Redhead (1994) presumed that this fungus could lead to a 20% reduction in green foliage in North America. Furthermore, it is being investigated as a possible bioherbicide for the management of ericaceous shrubs (Wilkin et al. 2005). If fields are not treated with fungicide, yield loss during the fruiting year can surpass 60% (Hildebrand & Renderos 2007). However, even in sprouts, yield can be affected by defoliation (Abbasi et al. 2023).

Type species: Valdensia heterodoxa Peyronel

Other species: This genus is monotypic.

Figure 1 – Valdensia heterodoxa. a Symptoms on leaves and fruit of Vaccinium angustifolium. b Mature and immature conida. c Teardrop-shaped conidium after downfolding of appendages. d Single series of closely packed transverse swellings (arrows) on proximal portion of upper surface of appendages. e Distal portion of appendage with subulate and sparsely granulate surface (arrows). Scale bars: b = 150 µm; c = 100 µm; d–e = 20 µm. Redrawn from Abbasi et al. (2023) and Nekoduka et al. (2012).

References

Gjerum HB. 1970 – A curious fungus on Vaccinium myrtillus. Blyttia, 3, 159–63.

Mulenko W, Woodward S. 1996 –Plant parasitic hyphomycetes new to Britain. Mycologist, 10(2), 69–x5.

Entry by

Herbert Dustin R. Aumentado, Center of Excellence in Fungal Research and School of Science, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, Thailand

(Edited by Ruvishika S. Jayawardena, Kevin D. Hyde, Samaneh Chaharmiri-Dokhaharani, & Achala R. Rathnayaka)

Published online 21 May 2024