Fungalpedia – Note 111 Juxtiphoma

Juxtiphoma Valenzuela-Lopez, Cano, Crous, Guarro & Stchigel

Citation when using this entry: Yasanthika et al., in prep – Genera of soil fungi. Mycosphere.

Index Fungorum, Facesoffungi, MycoBank, GenBank, Fig 1, 2.

Juxtiphoma (Didymellaceae, Pleosporales) was introduced by Valenzuela-Lopez et al. (2018) with the type species J. eupyrena (≡ Phoma eupyrena) based on multigene phylogeny (LSU, ITS, tub2 and rpb2) and morphological support. Three species have been accepted in this genus (Index Fungorum 2023). The asexual morph is characterized by brown pycnidial conidiomata with a wall of cells of textura angularis. Conidiogenous cells are phialidic, hyaline and ampulliform forming aseptate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, ovoid, ellipsoidal or cylindrical, biguttulate conidia. The sexual morph is undetermined (Domsch et al. 1993). Juxtiphoma is characterized by chlamydospores which are important for isolating species from soil particles. They are aseptate, ochraceous-brown, single or in chains, subglobose, barrel-shaped or ellipsoidal (Domsch et al. 1993, Valenzuela-Lopez et al. 2018). All species of this genus have been isolated from soil-based habitats (Yasanthika et al. 2021). Juxtiphoma eupyrena has been isolated from Solanum tuberosum and is commonly found in soils in the UK, India, Malaysia, Netherlands and the USA (Domsch et al. 1993). Juxtiphoma kolkmaniorum and J. yunnanensis have been described from garden soil in the Netherlands and industrial waste-contaminated soil in China (Hou et al. 2020, Yasanthika et al. 2021). Juxtiphoma is phylogenetically close to Cumuliphoma and morphologically similar in having pycnidia with hyaline conidia. However, Cumuliphoma lacks chlamydospores (Valenzuela-Lopez et al. 2018).

Type species: Juxtiphoma eupyrena (Sacc.) Valenz.-Lopez, Crous, Stchigel, Guarro & Cano

Other accepted species:

Juxtiphoma kolkmaniarum Hern.-Restr., L.W. Hou, L. Cai & Crous

Juxtiphoma yunnanensis Yasanthika, G.C. Ren & K.D. Hyde

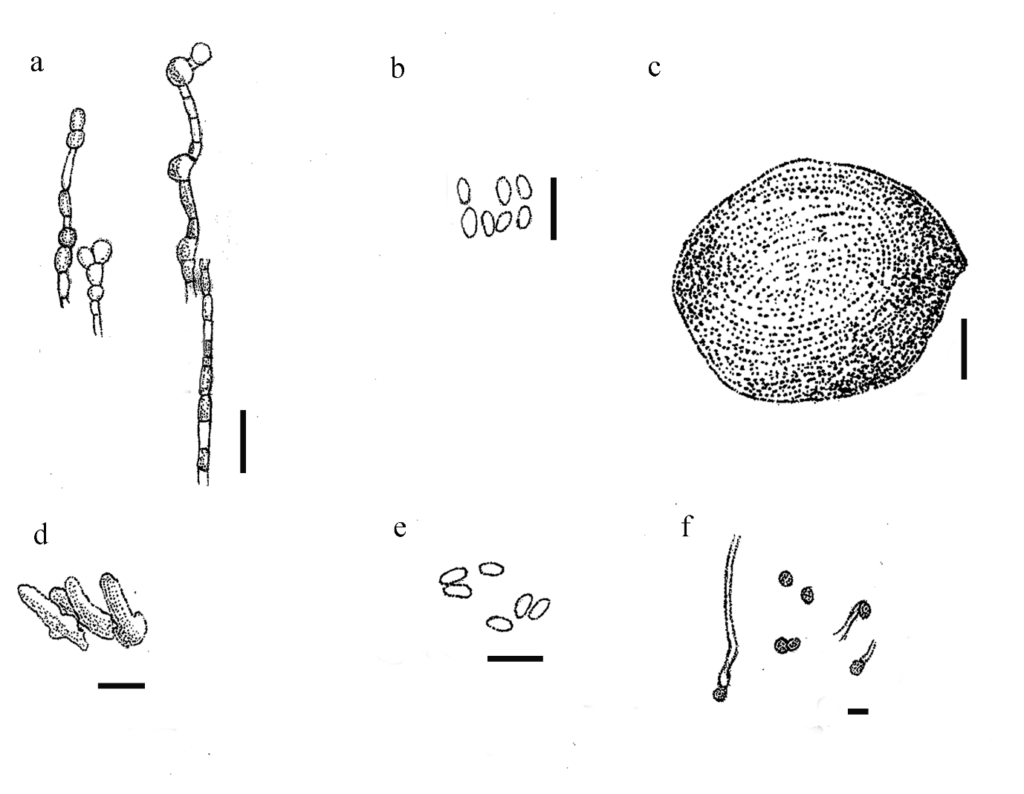

Figure 1 – Juxtiphoma eupyrena (redrawn from Fig. 280 in Domsch et al. 1993) a Chlamydospores. b Pycnoconidia. Juxtiphoma kolkmaniorum (CBS 146005) (redrawn from Hou et al. 2020). c Pycnidia forming on oatmeal agar. d Conidiogenous cells. e Conidia. f Chlamydospores. Scale bars: a, b = 500x, c = 100 µm, d-f =10 µm.

Figure 2 – Juxtiphoma yunnanensis (HKAS 107657) a Colony from above. b Colony from below. c Mycelia on the colony. d Mature septate hyphae. e Terminal, branched and chained chlamydospores. f–h Chlamydospores. Scale bars: d = 25 μm, e = 20 μm, f-h = 10 μm.

References

Bridge P, Spooner B. 2001 – Soil fungi: diversity and detection. Plant and Soil 232, 147–154.

Domsch KH, Gams W, Anderson TH. 1993 – Compendium of Soil Fungi. IHWVerlag Press.

Index Fungorum. 2023 – Available from: https://www.indexfungorum.org/names/names.asp (accessed on 20 April 2023).

Valenzuela-Lopez N, Cano-Lira JF, Guarro J, Sutton DA et al. 2018 – Coelomycetous Dothideomycetes with emphasis on the families Cucurbitariaceae and Didymellaceae. Studies in Mycology 90, 1–69.

Yasanthika E, Wanasinghe DN, Farias ARG, Tennakoon DS et al. Genera of soil Ascomycota. (in prep).

Entry by

Yasanthika W.A.E., Center of Excellence in Fungal Research, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, 57100, Thailand; School of Science, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, 57100, Thailand.

(Edited by Kevin D. Hyde)

Published online 21 September 2023